Legendary Nurse Marilyn Liota Looks Back—Part 3: The 1970s and 1980s

To celebrate VNSNY’s 125th anniversary, Frontline VNSNY is publishing a four-part reminiscence by legendary former VNSNY nurse, Marilyn Liota. During her six decades at VNSNY, from 1952 to 2012, Marilyn rose from a field nurse to become the Regional Administrator and Vice President for Home Care in Queens. During this time, she saw incredible changes, both in New York City’s patient population and at VNSNY.

To celebrate VNSNY’s 125th anniversary, Frontline VNSNY is publishing a four-part reminiscence by legendary former VNSNY nurse, Marilyn Liota. During her six decades at VNSNY, from 1952 to 2012, Marilyn rose from a field nurse to become the Regional Administrator and Vice President for Home Care in Queens. During this time, she saw incredible changes, both in New York City’s patient population and at VNSNY.

As you read these installments, we invite you to submit any questions you might have for Marilyn. Her replies will be posted as a special feature during National Nurses Week. Your questions can be emailed to Michael Delaney.

In this next installment, Marilyn recalls working for VNSNY in the 1970s and 1980s, as the organization expanded its scope and played a key role in the early days of the AIDS epidemic.

VNSNY in the 1970s and 1980s: Expanding Services and Taking the Lead in Caring for AIDS Patients

At the start of the 1970s, Marilyn had taken on additional administrative roles, but was also still working in the field as a frontline nurse. “That was the time when HMOs were on the rise, and more and more people had access to care,” she says. “VNSNY expanded its staff because we were starting to care for more people. At the same time, health care was beginning to cost more as reimbursements grew.”

The organization was expanding geographically, as well. In 1972, at Marilyn’s suggestion, VNSNY began offering services in Brooklyn, where it competed with the Brooklyn Visiting Nurse Association. “We started servicing Brooklyn, also known as Kings County, through the Queens border, using Queens staff,” Marilyn recalls. “We adopted the slogan, ‘The County of Queens Welcomes the County of Kings’ to advertise for additional nurses.”

The organization was expanding geographically, as well. In 1972, at Marilyn’s suggestion, VNSNY began offering services in Brooklyn, where it competed with the Brooklyn Visiting Nurse Association. “We started servicing Brooklyn, also known as Kings County, through the Queens border, using Queens staff,” Marilyn recalls. “We adopted the slogan, ‘The County of Queens Welcomes the County of Kings’ to advertise for additional nurses.”

As part of its expansion, VNSNY started adding clinicians from other disciplines to its staff as well. “We began to hire rehabilitation therapists in the 1970s, and later that decade we started a nurse practitioner training program with Cornell University,” says Marilyn. “We selected nurses from each office, who then studied at Cornell and New York Hospital to become nurse practitioners. When they began, the biggest area of need was wound care, and they did quite a bit of that. They were really the precursors of the wound ostomy nurses that VNSNY has today. But they also had the skills to do much more than that.” In New York, Marilyn notes, nurse practitioners have to work under the direction of the physician—“So our nurse practitioners became very good at setting up a treatment plan, then convincing their supervising doctor to prescribe that plan!”

In the late 1970s, Marilyn and her colleagues unexpectedly found themselves on the front lines of one of the biggest medical crises of the 20th century—the AIDS epidemic. Some of the first cases in the U.S. occurred in New York City under the care of VNSNY’s visiting nurses, although the true nature of the illness wasn’t apparent at first.

In the late 1970s, Marilyn and her colleagues unexpectedly found themselves on the front lines of one of the biggest medical crises of the 20th century—the AIDS epidemic. Some of the first cases in the U.S. occurred in New York City under the care of VNSNY’s visiting nurses, although the true nature of the illness wasn’t apparent at first.

“I was working as a nurse in Queens in the late 1970s,” says Marilyn, “when I and other VNSNY nurses across New York City began noticing that an unusually high number of male patients were dying from Kaposi’s sarcoma”—a rare and fast-moving cancer. By 1981, Kaposi’s sarcoma was spreading at an alarming rate, particularly among gay men. That year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced that these cancer cases were, in fact, part of a complex syndrome, HIV/AIDS, characterized by a complete breakdown of the immune system.

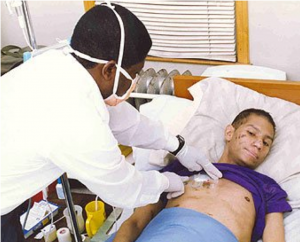

In addition to gay males, those at highest risk included individuals who were of Haitian descent or had hemophilia or used intravenous drugs. Fear of catching the newly discovered disease affected even medical professionals, some of whom were afraid to treat AIDS patients. At VNSNY, however, this was never a question: Adhering to its mission of caring for the vulnerable, the organization provided comprehensive education about the disease to its clinicians, who then played a lead role in caring for those swept up in the epidemic—a process that largely involved palliative care in the early years, when most victims died within a year or two of being diagnosed, due to a lack of effective medications. “We’ve always cared for patients whatever condition they might have,” says Marilyn. “In the AIDS epidemic, once we knew what we were dealing with, we used what we’d always used before—universal precautions. A patient is a patient. An illness is an illness.”

The Maternal Child Health team in Queens, 1990. From left to right: Karen Barefield, Roni Chassain, Carol Odnoha, Miriam Felix, Carol Wiener, Carol McNamara, Marilyn Liota, Pat Hidler, Marie Raganese, Nancy Archer, Lucille Albino, and Michelle Nation.

In the mid-1980s, it became clear that a growing number of women were contracting HIV/AIDS and transmitting it to their babies during childbirth. “This was an often-overlooked group,” notes Marilyn. “VNSNY’s Maternal Child Health program had just been launched, and the bulk of its patients were children with AIDS. The program’s funding went to provide direct care to these children, but it was never enough to cover the large numbers of sick children without private insurance. These children required around-the-clock care, and many were from single-parent homes. How could a parent care for their child, and also work and do everything else? It was impossible. So we provided pediatric respite care under the auspices of the Maternal Child Health program, which included training a home health aide to take care of these children. To help support this effort, we wrote targeted grant proposals, looking for funding from AIDS research sources. That program alone brought in two million dollars’ worth of grants.”

While pediatric AIDS would thankfully recede as a major health issue with the advent of new drugs and preventive measures, adds Marilyn, VNSNY continued to maintain its pediatric respite program in the ensuing years, offering around-the-clock care for children with other debilitating conditions.

To read Part 4: The 1990s and 2000s in our Marilyn Liota series, please click here.