Legendary Nurse Marilyn Liota Looks Back—Part 2: The 1960s

To celebrate VNSNY’s 125th anniversary, Frontline VNSNY is publishing a four-part reminiscence by legendary former VNSNY nurse, Marilyn Liota. During her six decades at VNSNY, from 1952 to 2012, Marilyn rose from a field nurse to become the Regional Administrator and Vice President for Home Care in Queens. During this time, she saw incredible changes, both in New York City’s patient population and at VNSNY.

To celebrate VNSNY’s 125th anniversary, Frontline VNSNY is publishing a four-part reminiscence by legendary former VNSNY nurse, Marilyn Liota. During her six decades at VNSNY, from 1952 to 2012, Marilyn rose from a field nurse to become the Regional Administrator and Vice President for Home Care in Queens. During this time, she saw incredible changes, both in New York City’s patient population and at VNSNY.

As you read these installments, we invite you to submit any questions you might have for Marilyn. Her replies will be posted as a special feature during National Nurses Week. Your questions can be emailed to Michael Delaney.

Last week, Marilyn looked back on the 1950s. In this week’s installment, Marilyn describes the impact of the turbulent 1960s on VNSNY and the home care profession.

VNSNY in the 1960s: A Decade of Change

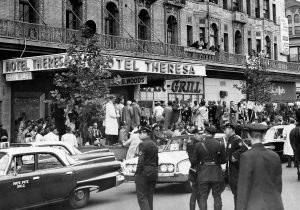

Like the U.S. as a whole, American health care underwent significant changes during the 1960s, and VNSNY changed with it. Marilyn began the decade working in Harlem, where she had a front-row seat for urban renewal’s razing of entire city blocks, and for Cuban premier Fidel Castro’s 1960 visit to New York City. In town for the opening session of the United Nations, Castro had chosen the Theresa Hotel on 125th Street as his headquarters, and luminaries from Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev to poet Alan Ginsburg traveled there to call on him. “I used to get my lunch at the Chock Full O’Nuts on the first floor of the Theresa Hotel,” says Marilyn. “I would eat my lunch and watch as this stream of people went into the hotel to see Castro.”

Crowd around and outside the Hotel Theresa at 125th Street and 7th Ave., where Fidel Castro stayed. If you look carefully on the right, there is the Chock Full O’Nuts where Marilyn watched!

From VNSNY’s standpoint, she adds, the decade’s most transformative change came when Medicare and Medicaid were signed into law in the mid-1960s. “Until those two programs went into effect, our services were funded by philanthropic donations and by collecting small fees from our patients. When I first started with VNSNY, we would collect 25 cents from each patient who could afford it. Then at some point that went up two dollars, and we were all horrified that the agency would charge so much.” The day Medicare and Medicaid were implemented, she remembers, “we stopped collecting fees. Suddenly we had substantial government support and were no longer totally dependent on charity for our operations, and that was monumental.”

President Johnson signing Medicare legislation into law in 1965.

As a result, says Marilyn, “we became larger and more financially secure. We still provided the same kind of care, but now we could bill for most of it. These programs also made new resources available to patients. Before, things like walkers and wheelchairs had to be purchased by families. Now, these were covered by Medicare and Medicaid.”

In addition to the introduction of Medicare and Medicaid, the mid-1960s was also the time when, spurred by the positive results being achieved with Thorazine and other newer psychotropic medications, New York State, along with the rest of the country, obeyed the federal mandate to end the mass institutionalization of its mentally ill population. It was a well-intentioned decision that produced problems of its own. “All of New York City’s mentally ill were discharged into the community without sufficient support,” says Marilyn. “Due to inadequate federal funding, New York State never established enough community mental health facilities for their large deinstitutionalized population. Our response was to develop support programs in adult homes and shelters. I started the first adult home program, where we provided nurses to adult homes and city shelters. Our public health nurses were still generalists at this time, so to keep them current we provided them with the education they needed to operate in facilities of that type.”

VNSNY was also playing a lead role in the latest emerging health care priority—proper deployment of the latest generation of oral tuberculosis medications. “The newer drugs were doing a good job of keeping tuberculosis under control without sending patients to sanitariums, but there were issues around people not taking the medications consistently over the full course of treatment,” says Marilyn. “So we were contracted by New York City’s health department to directly observe our preexisting patients and make sure they took their tuberculosis medications on a daily basis.”

Another key project VNSNY was involved with during this period was the 1963 launch of a home health aide (HHA) program. “Before that, patients who needed help with personal care used home attendants provided them by New York City,” Marilyn recalls. “We started a Medicare demonstration project in Queens, in which we hired local women and trained them to be HHAs.” Marilyn, just back from maternity leave, was appointed as program supervisor. “It was a radical change,” she says. “At first, we hired our own aides, but the need was so great that we began contracting with other organizations to supply HHAs.”

A VNSNY home health aide and nurse provide care to a patient in 1966.

Being able to provide people with additional HHA support was particularly important “if you were concerned about the nutritional or daily activity needs of someone living alone,” says Marilyn. “Prior to that, if you had a patient who had a stroke, for example, it would fall to the nurse to meet all that person’s needs. You would have to carry out a rehabilitation nursing plan in which you visited that patient several times a week and tried to do everything for the patient. Now, we had an important new resource. This program eventually led VNSNY to establish Partners in Care in 1983, which allowed us to employ and utilize our own home health aides.”

Following the demonstration project, Marilyn became a supervisor in Queens. At the time, VNSNY was taking steps to centralize its operations. “The smaller district offices were consolidated,” says Marilyn. “In Queens, we eventually moved to just one office. In order to stay attuned to the needs of the local communities, though, we created teams of nurses that covered certain geographic areas. So essentially we achieved the same goal with lower administrative costs.”

A visiting nurse in 1963, wearing the traditional VNSNY uniform.

As always, VNSNY’s caregivers continued to venture into every corner of the city to care for vulnerable New Yorkers of all backgrounds. One concession the agency did make to the changing times, notes Marilyn, was to shift from the formal attire that VNSNY nurses had traditionally worn toward more casual outfits. “Up until the late 1960s, our visiting nurses had very distinctive uniforms,” she says. “In the winter, we wore navy blue winter coats, and for the warmer months we had a simple navy-blue dress. We also wore VNSNY caps with badges on them, which had been designed by a famous hat maker.”

A computer from the 1960s.

During the late 1960s, recalls Marilyn, VNSNY also began developing automated patient records. “We were one of the earliest agencies to do this, long before we had our own IT department,” she says. “The computerized patient record represented the greatest single change in how we delivered home care. In the beginning, we weren’t sure that our nursing staff, many of whom were not computer literate, would be able to learn new skills, but the staff response was overwhelmingly positive. The automated systems revolutionized VNSNY’s care delivery in every way.”

To read Part 3: The 1970s and 1980s in our Marilyn Liota series, please click here.