Black History Month at VNSNY: Meet Jessie Sleet Scales, the First African American Public Health Nurse

As part of VNSNY’s recognition of Black History Month, Frontline is featuring profiles of several pioneering African American nurses. Today’s profile, the first in the series, spotlights Jessie Sleet Scales, the first African American Public Health Nurse. To read the profile of Elizabeth Tyler, VNSNY’s first African American nurse, click here. To read the profile of Edith Carter, VNSNY’s second African American nurse, click here.

As part of VNSNY’s recognition of Black History Month, Frontline is featuring profiles of several pioneering African American nurses. Today’s profile, the first in the series, spotlights Jessie Sleet Scales, the first African American Public Health Nurse. To read the profile of Elizabeth Tyler, VNSNY’s first African American nurse, click here. To read the profile of Edith Carter, VNSNY’s second African American nurse, click here.

Jessie Sleet Scales was born in Ontario, Canada just as the American Civil War was ending in 1865, and would go on to help found the Stillman House Settlement—a branch of VNSNY (known then as the Henry Street Settlement Visiting Nurse Service) on Manhattan’s West Side.

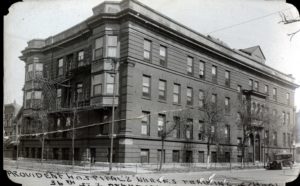

Provident Hospital School of Nursing, Chicago

In 1895, Jessie graduated from the Provident Hospital School of Nursing in Chicago—the first African American-owned and operated hospital in America, and the first to host a school dedicated towards educating Black women in nursing, during a time in American history where few public or private medical facilities were open to Black Americans. She continued her education at Freedman’s Hospital in Washington D.C., which would later become one of the teaching facilities for Howard University Medical Center. Determined to work in the field of public health to provide care for underserved members of society, and learning of the lack of African American representation among nurses in New York City, Jessie made her way north to seek employment. Upon her arrival in New York City in 1900, she found herself among a population especially hard hit by another contemporary public health crisis: tuberculosis.

The 19th-century shift in population from country to city that accompanied industrialization and immigration led to overcrowding and poor, unsanitary living conditions, which resulted in repeated outbreaks of diseases such as cholera, influenza, and tuberculosis. While public health improvements had begun to take shape at the dawn of the 20th century, tuberculosis remained one of the leading causes of death in America, claiming the lives of 194 of every 100,000 U.S. residents, most of whom lived in urban areas like New York, where the African American population found itself especially hard hit. Public health workers like Jessie were desperately needed to help stem the tide of the disease—yet even with the breadth of nursing knowledge she had under her belt, she was met with numerous hurdles as an African American in health care at the turn of the century, and spent months looking for employment.

On October 3, 1900, after being rejected by a number of institutions in Manhattan and Brooklyn, Jessie finally managed to a secure a two-month “experimental” position as a district nurse—essentially an early term for a public health nurse—with the Charity Organization Society (COS). Noting the high incidence of tuberculosis within the African American population in New York City, the COS decided a Black nurse could better address the specific needs of the community and persuade people to seek assistance, at a time when the city’s African American community had a deep-seated resistance to formal medical care. In her position at COS, Jessie served as the first Black public health nurse in the United States.

Records from that time show the wide range of health conditions that Jessie was addressing. In a single two-month period, her caseload included visits to forty-one families throughout New York City, making a total of 156 house calls. A self-written report of her work, entitled “A Successful Experiment,” was published by the American Journal of Nursing, whose editor commended her on her extraordinary capabilities. Aside from tuberculosis, Jessie recounted many other afflictions she encountered among her patients, writing:

“I cared for nine cases of consumption, four cases of peritonitis, two cases of chickenpox, two cases of cancer, one case of diphtheria, two cases of heart disease, two cases of tumor, one case of gastric catarrh, two cases of pneumonia, four cases of rheumatism, and two cases of scalp wound. I have given baths, applied poultices, dressed wounds, washed and dressed newborn babies, and cared for mothers.”

Her tireless efforts did not go unnoticed, and the COS eventually granted her full employment. Jessie continued her work with the society for nine years, but all the while she envisioned a greater plan to help those most in need, and looked towards creating a physical location to take care of the sick on the West Side of Manhattan.

Jessie’s growth in the field of nursing led her to meet Lillian Wald, the founder of VNSNY and the Henry Street Settlement on New York’s Lower East Side. It was Jessie who introduced Lilian to Elizabeth Tyler, a fellow Black nurse who had also studied at the Freedman’s Hospital in Washington D.C., suggesting that she work directly with African American patients at the Henry Street Settlement. Lillian recognized the opportunity to provide this much needed, culturally appropriate care, and hired her based off Jessie’s recommendation, thereby making Elizabeth the very first African American nurse employed by VNSNY and the Henry Street Settlement.

Jessie and Elizabeth’s contributions to the organization and the people of New York did not end there, however. In December 1906, together with Edith Carter, the first African American nurse to provide primary maternal and infant care in New York City, Jessie and Elizabeth successfully established the physical location Jessie had long envisioned: a new branch of the Henry Street Settlement known as the Stillman House.

San Juan Hill

The Stillman House was located in the heart of what was then known as San Juan Hill, a diverse community that was home to thousands of mostly Black immigrants, stretching from the West 50s up through the West 60s in Manhattan. The neighborhood was plagued by crowded, unsanitary living conditions and a high mortality rate, and was desperately in need of community-based health resources to combat the diseases running rampant.

Considered the nation’s first public health clinic established specifically for African Americans, the Stillman House filled this role. Jessie and the Henry Street Settlement immediately began providing excellent nursing care to relieve the beleaguered neighborhood. Meeting with great success, the House grew in size, relocated, and also expanded its social services for the community to include a library, instructional classes, and clubs.

By delivering essential services which met the specific social and cultural needs of New York’s African American community, Jessie Sleet Scales exemplified the cultural competency so crucial to today’s modern heath care setting. The pioneering work she carried out along with the Henry Street Settlement would inspire other organizations to hire Black community health nurses, helping to bridge a deep racial divide pervasive in the field.

It is safe to say that Jessie’s own view of her role as a community care giver echoes the sentiments of health care workers today, who themselves are fighting against a new public health crisis, COVID-19, with the same steadfast dedication as the nurses of VNSNY over a century ago. In closing her American Journal of Nursing Report, Jessie wrote: “I cannot but feel that this house-to-house visiting, these face-to-face practical talks, which I am having with the people, must bring about good results.”

It is safe to say that Jessie’s own view of her role as a community care giver echoes the sentiments of health care workers today, who themselves are fighting against a new public health crisis, COVID-19, with the same steadfast dedication as the nurses of VNSNY over a century ago. In closing her American Journal of Nursing Report, Jessie wrote: “I cannot but feel that this house-to-house visiting, these face-to-face practical talks, which I am having with the people, must bring about good results.”